We’re pretty sure everyone has heard the story of a famous “Nigerian prince” before. It’s one of the stereotypes used to describe Nigerians because of how rampant cybercrime is in the country. But that’s not what the story here is about. Actually, the kidnapped African prince is a story of bravery, resilience, and hope. It’s an account of a young prince who was taken from his African home and sold into slavery. The odds were certainly stacked against him. But he escaped and made his way to freedom. The road to liberty is what makes this story worth telling.

This story is an excellent example of human strength and determination. It is also a reminder of the importance of never giving up, no matter how difficult the situation may seem. They say you never know how strong you are until being strong is your only option. So, who was the kidnapped African prince?

Who Was the Kidnapped African Prince?

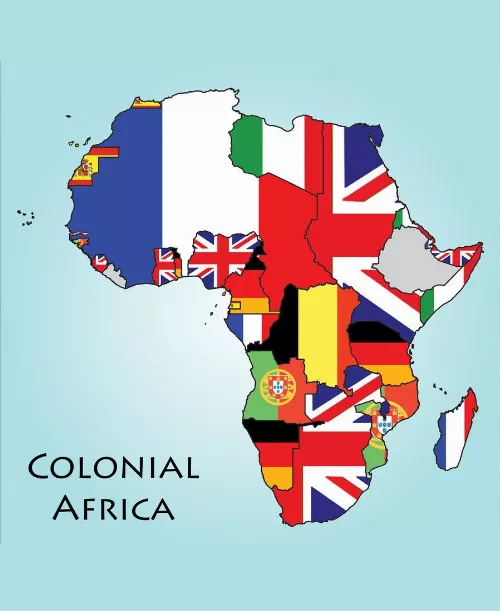

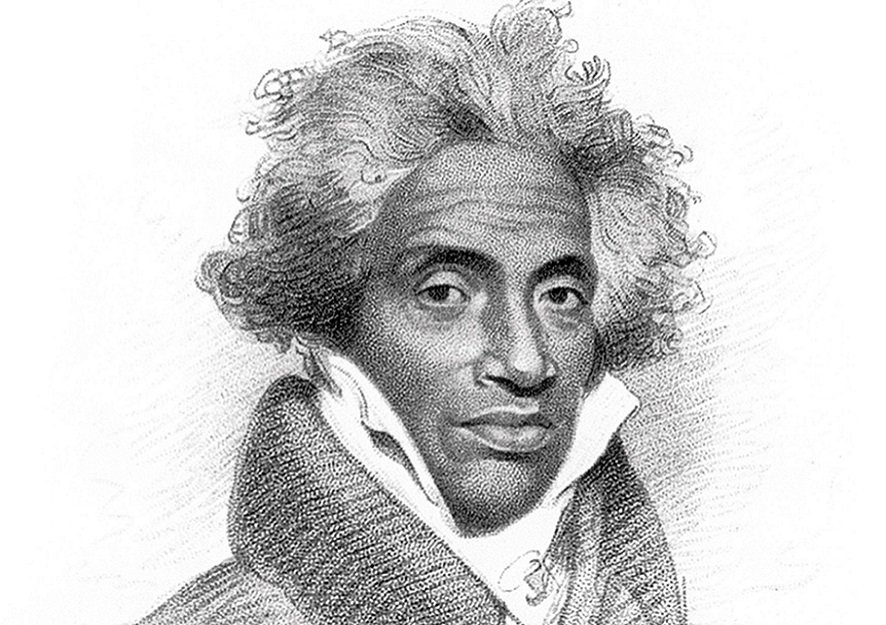

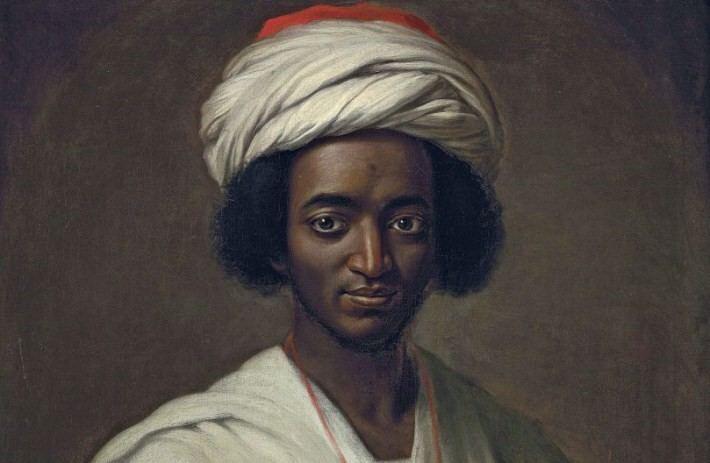

In 1788, Abdul Rahman Ibrahima ibn Sori, a prince and Amir (commander) from the Guinean Fouta Djallon region, was kidnapped. He was then sold to slave traders who took him to the United States. After learning of his ancestry, Abdul Rahman’s slave master Thomas Foster started calling him “Prince.” This was a title he kept up until his death.

However, he was set free in 1828 after 40 years of servitude, and he went back to Africa the next year. But unfortunately, he passed away in Liberia not long after his arrival. Slavery was so widespread that you don’t always get specific accounts of people sold into servitude. Especially when they were Muslim slaves, like Sori.

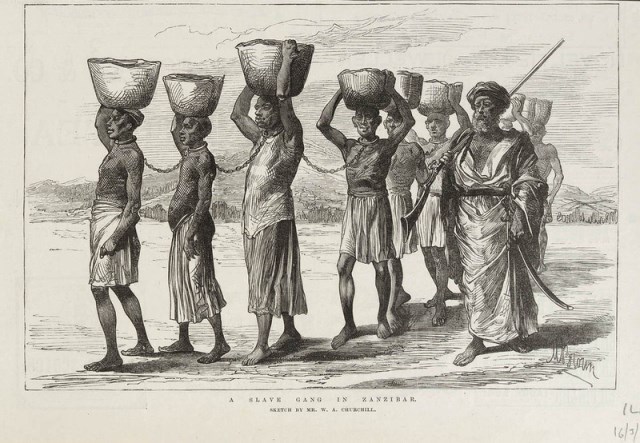

Despite the enormity of the slave trade—Sori was one of 12.5 million Africans forcibly removed from their homes and sold to a New World between 1525 and 1866. He was an anomaly, an aristocrat with a high level of education. His dramatic fight for freedom would eventually make him a household name. Hence, his astonishing life has more documentation than others.

Abdul Rahman Ibrahima Sori’s Early Life

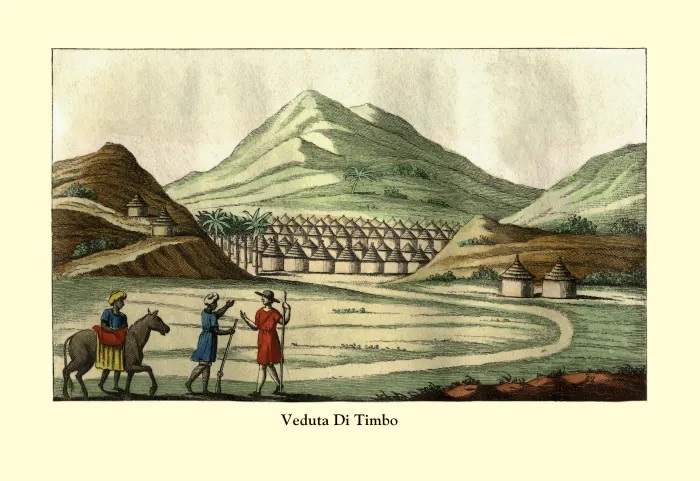

Born in Timbuktu in 1762, Abdul Rahman Ibrahima was a Torodbe Fulani Muslim prince. He was the son of Ibrahima Sori and his Moorish wife. When he was five years old, his father transferred the family from Timbuktu to Timbo, which is today in Guinea.

In 1776, Ibrahima consolidated the Islamic confederation of Fouta Djallon, making Timbo its capital and finally succeeding as its Almamy. Speaking at least four African languages, including Bambara, Fula, Mandinka, and Yalunka, in addition to Arabic, Abdul Rahman studied in madrasahs in Timbuktu and Djenné. He joined his father’s army in 1781 after returning to his own country. He was promoted to regimental commander (Amir) for a campaign to subdue the Bambara and for a campaign against the “Hebohs.”

The Hebohs had been bothering the European ships that carried out the Fulani trade in war-captive slaves and the crops to sustain them across the Middle Passage. Abdul Rahman was given command of 2000 cavalry troops in 1788. And although he originally fought the Hebohs, they later ambushed his cavalry in the mountains. When Abdul Rahman refused to run, he was shot, taken prisoner, and sold into slavery.

Prince Abdul Rahman Ibrahima Sori Sold Into Slavery

After being taken hostage by hostile forces in 1788 in his home Fouta Djallon in what is now Guinea, Sori was taken to Natchez, Mississippi. At the peak of the global slave trade, when about 80,000 Africans were being captured, shackled, and transported across the Atlantic Ocean every year—the powerful prince was traded to slave traders for a few muskets, eight hands of tobacco, two flasks of powder, and rum.

He was transported from Dominica via New Orleans to Natchez, Mississippi. There, he and another slave were sold to Thomas Foster for roughly $950. Afterward, he made an early unsuccessful attempt to flee. But in the end, he worked for more than 38 years before getting his freedom.

During his slavery years, he married Isabella, a different Foster slave, on Christmas Day 1794. And they eventually had nine children together. By 1797, Isabella would become a Baptist, and by 1818, Abdul Rahman was attending services regularly with his family. However, he continued to object to those aspects of Christianity that went against the Islamic faith he was raised with. Particularly the doctrine of the Trinity. He also criticized how Christianity was practiced in the context of American plantation slavery.

The African Prince Abdul Rahman Ibrahima Sori’s Early Escape

As an African prince, Sori’s long hair, considered a sign of royalty in Fouta Djallon, was swiftly cut off by Foster. He was then made to perform rigorous manual labor. Abdul Rahman Sori decided to flee rather than endure the humiliation. He made it through weeks in a hostile, difficult environment. During that period, wanted posters sprung up, and he was the target of fruitless searches by slave hunters.

It took little time for the man to ultimately see there was no way out. It was also the moment he understood he would never be able to go back to Fouta Djallon. With no other viable options, Sori went back to Foster and started working on becoming indispensable. He had to win back his master’s trust, accept Christianity to make him happy, and become focal to his business.

Foster was an ignorant cow herder and tobacco farmer who had little knowledge of cotton, a commodity that was becoming more important in North America. However, Sori did know about cotton since Fouta Jallon was a cotton-growing region. With Sori’s help, Foster rose to prominence as one of the region’s top cotton producers. And as a result, Sori’s power also increased as his plantation grew.

Slavery and Struggle for Freedom

Abdul Rahman Sori was regarded as loyal and trustworthy by the other slaves on the plantation. And because of his skill in managing cattle and overseeing other slaves’ work in the cotton harvest, he gained the respect of his fellow slaves. He was given permission to walk to a nearby market in Washington, Mississippi, to sell vegetables. Later, he was surprised to run into Dr. John Coates Cox, an old friend, there in 1807.

Cox had been working as a surgeon on an English ship off the coast of West Africa in the 1780s when his ship abandoned him after he got lost, got hurt on land, and needed medical attention. At that time, he was saved and carried as a curiosity to Timbo. There, he recovered and lived with Abdul Rahman’s family for six months before being escorted back to the coast to find transportation home. He and Abdul Rahman Sori reconnected decades later after randomly running into each other at the Washington market.

Read: The Transatlantic Slave Trade and Its Impact Today

Cox Tries to Save Sori From Foster

On gaining knowledge of Sori’s situation, Cox offered $1000 to buy the African prince from Foster. He wanted him to travel back to his native Africa. Cox even went as far as persuading the governor of Mississippi to support his proposal. Foster, however, refused to sell Abdul Rahman because he saw him as essential to the plantation. Especially given his positive influence on the other slaves.

Before he died in 1816, Cox persisted in trying to free Abdul Rahman. But it was fruitless. However, his son William Rousseau Cox once more tried to buy and free the slave after his father’s death but was also turned down. Sori wrote a letter to his family in Arabic in 1826 with Andrew Marschalk’s support.

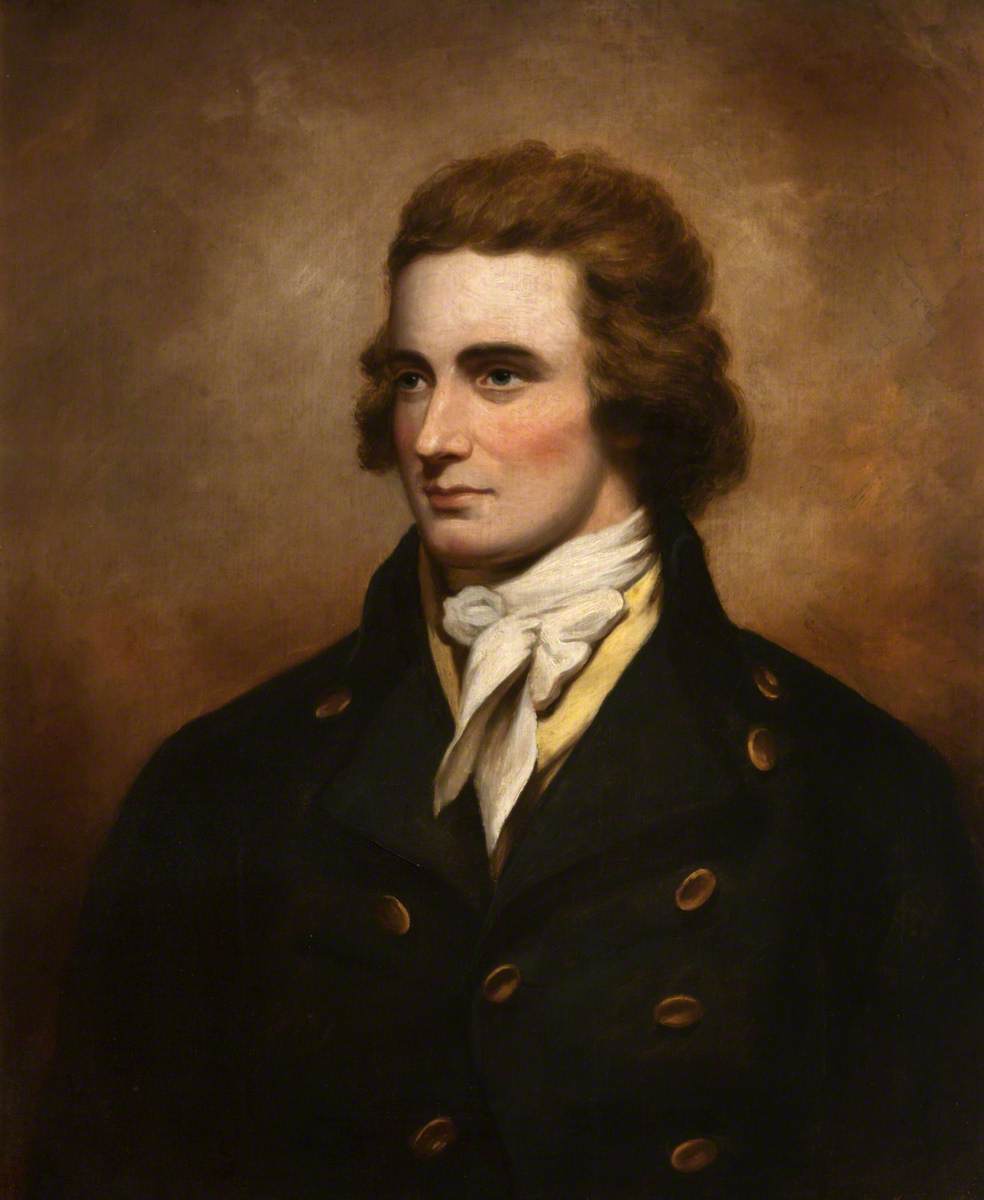

This letter was sent to the American Consulate in Morocco through United States Senator Thomas Reed. The letter was given to Sultan Abderrahmane II by the consul. Then he begged President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of State Henry Clay to mediate for Abdul Rahman’s freedom. However, this would be done in exchange for the release of numerous Americans who were being detained against their will in his nation.

After this intervention, Thomas Foster, in 1828, consented to Abdul Rahman’s release without compensation, giving him over to Marschalk and his wife. They subsequently set him free with the condition that he be transported to Africa by the government. Foster additionally gave Marschalk permission to pay $200 in donations – from Natchez residents to buy Isabella at a discount and set her free. From there, they went to Baltimore, where he met Clay. On May 15, Sori met with President Adams. And he stated his desire for his five sons and eight grandchildren to become free. Afterward, he described his encounter in a letter to his children in Mississippi.

Freedom and Death of the Infamous African Prince

Before leaving the country, Abdul Rahman and his wife undertook a 10-month tour. This included going through several northern towns to garner support for his family’s release from Natchez. They did this through the press, personal appearances, the American Colonization Society, and politicians.

On February 9, 1829, Abdul Rahman and Isabella boarded the Harriet from Norfolk, Virginia. They traveled without their family because they had only raised $4000 of the projected $10,000 needed to rescue their children and grandchildren. The American Colonization Society had paid for this group of freemen’s trip to Liberia. After arriving, Abdul Rahman wrote to America to request money to liberate his children, to explain his plans to develop trade with his motherland, which he intended to visit, and to report that he was “unwell, but much better.”

Put Your Tech Company on the Map!

Get featured on Nicholas Idoko’s Blog for just $50. Showcase your business, boost credibility, and reach a growing audience eager for tech solutions.

Publish NowAlthough he had received assistance and transportation under the guise of having embraced Christianity, – “as soon as he got in sight” of Africa, he switched back to practicing Islam wholeheartedly. On July 6, 1829, at the age of roughly 67, he and 30 other passengers from the Harriet died amid a yellow fever epidemic that was ravaging the area. Hence, he would never see Fouta Djallon or his children again.

Before you go…

Hey, thank you for reading this blog to the end. I hope it was helpful. Let me tell you a little bit about Nicholas Idoko Technologies. We help businesses and companies build an online presence by developing web, mobile, desktop, and blockchain applications.

As a company, we work with your budget in developing your ideas and projects beautifully and elegantly as well as participate in the growth of your business. We do a lot of freelance work in various sectors, such as blockchain, booking, e-commerce, education, online games, voting, and payments. Our ability to provide the needed resources to help clients develop their software packages for their targeted audience on schedule is unmatched.

Be sure to contact us if you need our services! We are readily available.

[E-Books for Sale]

1,500 AI Applications for Next-Level Growth: Unleash the Potential for Wealth and Innovation

$5.38 • 1,500 AI Applications • 228 pages

Are you ready to tap into the power of Artificial Intelligence without the tech jargon and endless guesswork? This definitive e-book unlocks 1,500 real-world AI strategies that can help you.

See All 1,500 AI Applications of this E-Book

750 Lucrative Business Ideas: Your Ultimate Guide to Thriving in the U.S. Market

$49 • 750 Business Ideas • 109 pages

Unlock 750 profitable business ideas to transform your future. Discover the ultimate guide for aspiring entrepreneurs today!

See All 750 Business Ideas of this E-Book

500 Cutting-Edge Tech Startup Ideas for 2024 & 2025: Innovate, Create, Dominate

$19.99 • 500 Tech Startup Ideas • 62 pages

You will get inspired with 500 innovative tech startup ideas for 2024 and 2025, complete with concise descriptions to help you kickstart your entrepreneurial journey in AI, Blockchain, IoT, Fintech, and AR/VR.

We Design & Develop Websites, Android & iOS Apps

Looking to transform your digital presence? We specialize in creating stunning websites and powerful mobile apps for Android and iOS. Let us bring your vision to life with innovative, tailored solutions!

Get Started Today