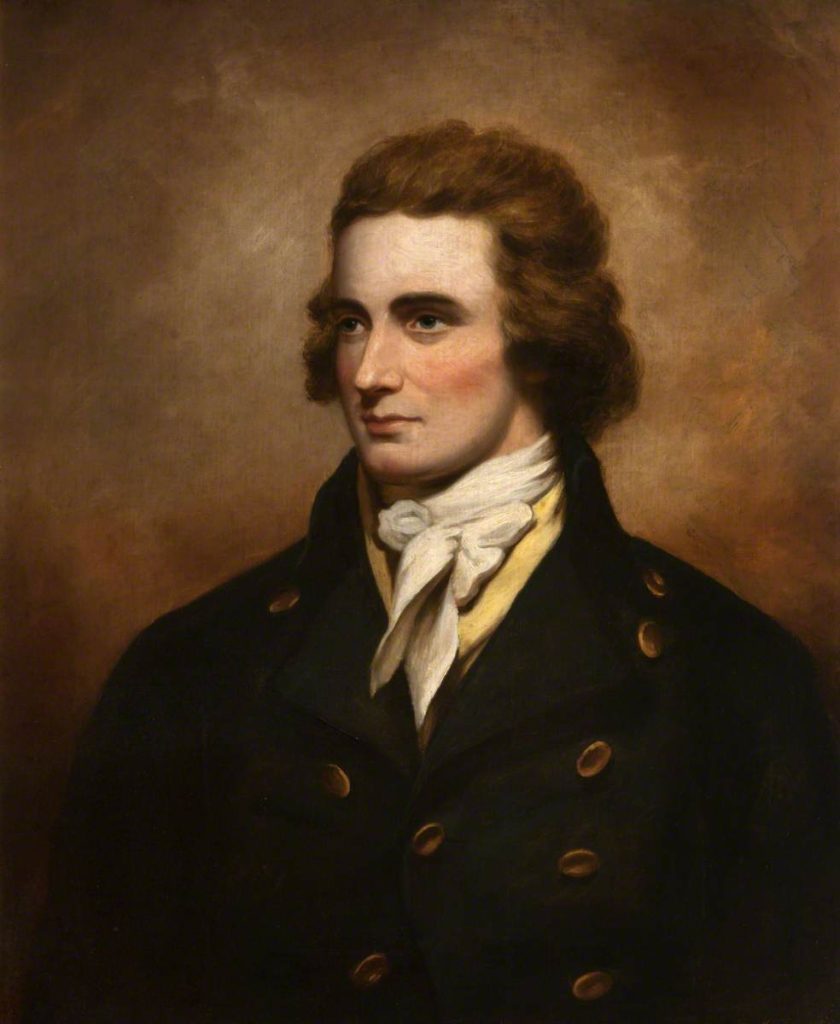

Mungo Park was a Scottish explorer who made several expeditions to Africa in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He is best known for his journeys to the Niger River, which he documented in his book Travels in the Interior of Africa.

Park’s travels helped dispel the myths about Africa that were popular then. And he is credited with opening up the continent’s interior to European exploration.

In recent years, however, Park’s legacy has come under scrutiny. Some historians have accused him of plagiarism, exaggeration, and even fabricating some of his stories. This article will explore the truth about Mungo Park and his discoveries in Africa.

Who Was Mungo Park?

Mungo Park, originally from Scotland, was an adventurous and brave wanderer and explorer. During the turbulent 18th century, he visited West Africa. He became the first Westerner to journey to reach the center Niger River. During his brief life, he was imprisoned by a Moorish chief. He endured innumerable difficulties and traveled hundreds of miles within Africa and worldwide. Park succumbed to sickness and folly and was even falsely assumed dead. His life was short but full of adventure, risk, and dedication. He is rightly known as an adventurer on par with Captain Cook and Ernest Shackleton.

Mungo Park – Early Life and Education

Mungo Park was born in Selkirkshire in Foulshiels on the Yarrow, near Selkirk, on a tenant farm rented from the Duke of Buccleuch by his father. He was the seventh of thirteen children. Despite being tenant farmers, the Parks were fairly well-off. They could pay for Park’s schooling, and when Park’s father died, he left behind properties worth £3,000.

Park was educated at home before attending Selkirk Grammar School. And at 14, he began an apprenticeship with a surgeon named Thomas Anderson in Selkirk. During his training, he befriended Anderson’s son Alexander and became acquainted with his daughter Allison. She would later become his wife. Park began studying medicine and botany at the University of Edinburgh in October 1788.

While studying at the university, he took Prof John Walker’s natural history course for a year. After finishing his studies, he spent a summer in the Scottish highlands doing botanical fieldwork with his brother-in-law, James Dickson. Dickson was a botanist who began his career as a gardener and seed seller in Covent Garden. In 1788, he and Sir Joseph Banks, who served as James Cook’s scientific adviser on his round-the-world journey from 1768 to 1771, created the London Linnean Society. Park completed his medical study by passing an oral examination at the College of Surgeons in London in January 1793. In February 1793, Worcester set sail for Benkulen, Sumatra.

Park gave a talk to the Linnaean Society upon his return in 1794, describing eight new Sumatran fish. The paper was not published for another three years. He also sent Banks several rare Sumatran flora.

Mungo Park’s Expeditions to Africa’s Interior

In 1794, Park offered his services to the African Association, which was looking for a replacement for Major Daniel Houghton. The latter had been dispatched in 1790 to discover the course of the Niger and had died in the Sahara. Banks was a founding member of the Association, founded in 1788 to ‘increase knowledge’ of Africa and ‘grow rich, or rather richer.’

Innovative Tech Solutions, Tailored for You

Our leading tech firm crafts custom software, web & mobile apps, designed with your unique needs in mind. Elevate your business with cutting-edge solutions no one else can offer.

Start NowPark was chosen with the help of Sir Joseph Banks. He was paid 271 pounds yearly to travel as far up the Niger River as he could before exiting through the Gambia.

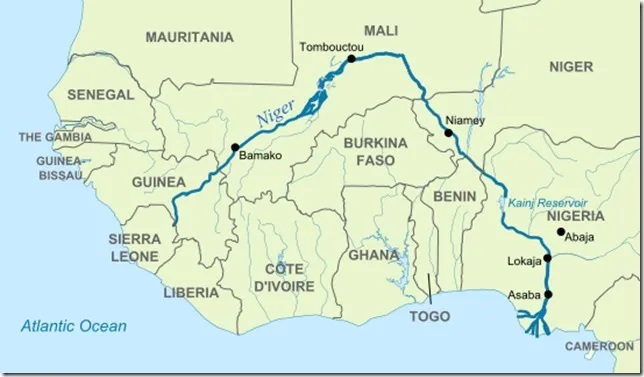

On June 21, 1795, he arrived at the Gambia River. Then, he sailed upstream for 200 miles to the British trading post of Pisania. On December 2, he set out for the undiscovered interior, accompanied by two native guides. He chose the path that passed across the upper Senegal basin and the semi-desert region of Kaarta.

The journey was tough, and he was imprisoned for four months by the local chief at Ludamar. On July 1, 1796, he escaped alone with nothing except his horse and a pocket compass. And on the 21st of the same month, he became the first European to reach the long-desired Niger at Segu.

He followed the river downstream for 80 miles to Silla. Here, he was forced to turn around due to a shortage of resources. On his return journey, which began on July 30, he took a more southern path than he had initially taken. He stayed close to the Niger, as far as Bamako, thereby tracing its course for 300 miles. But he became ill in Kamalia. Fortunately, a man saved his life, housing him for seven months.

Mungo Park’s Return to Pisania and Subsequent Quests

Mungo Park eventually returned to Pisania on June 10, 1797, returning to Scotland through America on December 22. He had been presumed dead, and his return home with news of the Niger’s discovery sparked widespread public excitement.

Park married Allison, the daughter of his old master, Thomas Anderson, in August 1799 after settling in Foulshield. Banks intended to engage Park in an expedition to explore Australia. But his wife was not interested, so Park declined the offer, distancing himself from his old patron. Park relocated to Peebles, where he worked as a doctor and surgeon after becoming completely certified in 1799.

In 1893, however, he was commissioned by the African Association to ‘map the complete course of the Niger.’ Allison remained reluctant, but the compensation was more appealing this time (5,000 for expenditures and a thousand per year), and he began to prepare himself by studying Arabic.

His teacher was Sidi Ambak Bubi, a Mogador native whose antics both entertained and scared the residents of Peebles. Park returned to Foulshiels in May 1804 and met Sir Walter Scott, who was then staying nearby at Ashesteil and with whom he quickly became friendly.

In September, he was summoned to London to depart on the next voyage; he left Scott with the hopeful saying, “Freits (omens) follow those who look to them.” Park had adopted the belief that the Niger and Congo rivers were one, and in a memorandum written before leaving Britain, he wrote, “My hopes of returning by the Congo are not altogether fanciful.”

Park’s Attitude Toward Africans

At the beginning of his voyage, Park seemed to get along well with the Africans he met. However, he disliked the Arab Tuareg, believing them savage, lacking any ‘spark of humanity.’ He seemed to have been quite hostile toward them, firing at anyone he perceived to be a threat.

Heinrich Barth, who later arrived in Timbuktu, was regaled with tales of “that Christian traveller, Mungo Park, who had arrived on the Niger some 50 years ago appearing seemingly out of nowhere, to the consternation of the natives” and whose “policy it was to fire at anyone who approached him with a threatening attitude,” killing some.

Mungo Park Embarks on His Second Journey

On January 31, 1805, he embarked from Portsmouth for The Gambia, having been given a captain’s commission as the leader of the government expedition.

Alexander Anderson, his brother-in-law, was second in command and was given the rank of lieutenant. George Scott, a Borderer, was the draughtsman, and there were four or five artificers in the party. Park was joined in Goree (then under British occupation) by Lieutenant Martyn, R.A., 35 privates, and two seamen.

The expedition arrived in Niger in the middle of August with just eleven Europeans still alive; the remainder had died of disease or dysentery. The travel from Bamako to Segu was completed by canoe. Park prepared for his expedition down the still undiscovered section of the river after receiving permission from the local king to continue at Sansandig, a bit below Segu.

Park transformed two canoes into a tolerably nice boat, 40 feet long and 6 feet wide, with the assistance of one soldier, the only one still capable of labor.

Mungo Park’s Death and Legacy

He wrote to his wife that he would not rest or land anywhere until he reached the shore, where he anticipated to arrive towards the end of January 1806. These were Park’s final messages, and nothing more was heard of the party until disaster news reached The Gambia’s settlements.

Finally, the British government dispatched Isaaco, a Mandingo guide who had worked with him for a while, to Niger to establish the explorer’s fate. At Sansandig, Isaaco discovered the guide who had gone downstream with Park, and the major truth of the tale he gave was later confirmed by Hugh Clapperton and Richard Lander’s investigations.

Allison Park, Park’s wife, died in 1840. Mungo Park’s exploits stimulated European appetites for African exploration, becoming almost mythical. Others of a similar low socioeconomic level were motivated by him to try their luck in Africa. Kryza writes of a new type of European hero.

This lone, brave African explorer penetrates the heart of the continent with the sole purpose of finding out what is there to be found, whose tales of their own exploits soon “captured the imagination, fed the fantasies, and filled the literature of Europe.”

Seamless API Connectivity for Next-Level Integration

Unlock limitless possibilities by connecting your systems with a custom API built to perform flawlessly. Stand apart with our solutions that others simply can’t offer.

Get StartedBefore you go…

Hey, thank you for reading this blog to the end. I hope it was helpful. Let me tell you a little bit about Nicholas Idoko Technologies. We help businesses and companies build an online presence by developing web, mobile, desktop, and blockchain applications.

We also help aspiring software developers and programmers learn the skills they need to have a successful career. Take your first step to becoming a programming boss by joining our Learn To Code academy today!

Be sure to contact us if you need more information or have any questions! We are readily available.